Audio Essay: Political Culture and Elections

Melinda Jackson, San Jose State University

Introduction

Terms:

- Political socialization

Section 1: Political Socialization and Values

Section Question:

How do Americans become politically socialized, and how do they vote?

Question:

What does it mean to become politically socialized?

Terms:

- Ways of political socialization

- Agents of political socialization

- Political pundits

Agents of Political Socialization

Presidential TV Campaign Ads

Question:

What general political values do Americans have?

Terms:

-

Core set of values

-

Presidential TV campaign ads

-

The American’s Creed

-

Impediments to voting

-

William Tyler Page

-

Equality of opportunity

Civic Values, United States and Global Median, 2015

Federal Agencies that Ensure Equality of Opportunity: One way that America attempts to ensure equality of opportunity for its citizens is through legislation. Education, housing, and employment are key avenues to the American goal of giving equal access to resources and creating a level playing field.

Voter ID Laws, 2015

Question:

How do American vote?

Terms:

-

Voting rights by state

-

Percent of adults who could name the branches of government

-

Frequency and number of elections

-

Ballot initiatives

-

Direct democracy

-

Open primaries

-

Closed primaries

-

Hybrid model primaries

-

Top-two primaries

-

Early primary states

-

Senate seats up for election

-

House seats up for election

-

General election

-

Midterm election

Hybrid model primaries represent some combination of the open and closed primary models described above. Exact rules vary from state to state, and in some states requesting a party primary ballot serves as your official declaration of party voter registration. Twenty-four states currently use some form of hybrid model for their primary elections.

General and Midterm Elections

Primary elections take on additional importance in the presidential election cycle, with the states that hold their primaries early receiving greater attention from the candidates. The presidential primary election calendar is determined by the national party organizations, but traditionally the Iowa caucuses (an in-person discussion-based voting process) and New Hampshire primaries have always been the first of the election year, therefore receiving a disproportionate share of attention from presidential candidates of both parties. Generally speaking, the earlier in an election year a state’s primaries are held, the more influence they will hold over the outcome. However, in a very close primary election contest, states that vote later may hold more sway over the final outcome.

Section 2: Elections in America

Section Question:

What are the unique qualities of American elections?

Question:

How does the Electoral College system work?

Terms:

-

Electoral College

-

Determining the number of Electoral College votes

-

Senate elected by state legislatures

-

Makeup of the Electoral College

-

Battleground states

-

270/538 Electoral College votes

-

Unit rule vs. proportional rule

Electoral College Votes Allotted by State and District, 2012

A great deal of attention is focused on the “red” vs. “blue” states in the Electoral College map in every presidential election. But in fact the most attention is reserved for the handful of states — usually 8 to 10 — that will make the difference in reaching the magic number of 270 Electoral College votes for one candidate or the other, and thereby determine the winner of the US presidency.

Nearly all states follow the unit rule, meaning that they award all of their Electoral College votes to the candidate who wins the most votes in that state. This is truly a “winner-take-all” system, in which the candidate with a plurality of the vote takes the entire electoral prize for that state, while the second place candidate gets nothing.

Pivotal States, Presidential Election, 2012

Question:

How do campaigns strategize with the Electoral College vote?

Terms:

-

Differences in the popular vote vs. the Electoral College vote

-

“Red” vs. “blue” states

-

Swing states

-

The Electoral College in the 2012 presidential election

-

Changing the Electoral College

-

The Electoral College in the 2000 presidential election

Presidential Election Results, 1992

“Red” and “Blue” States

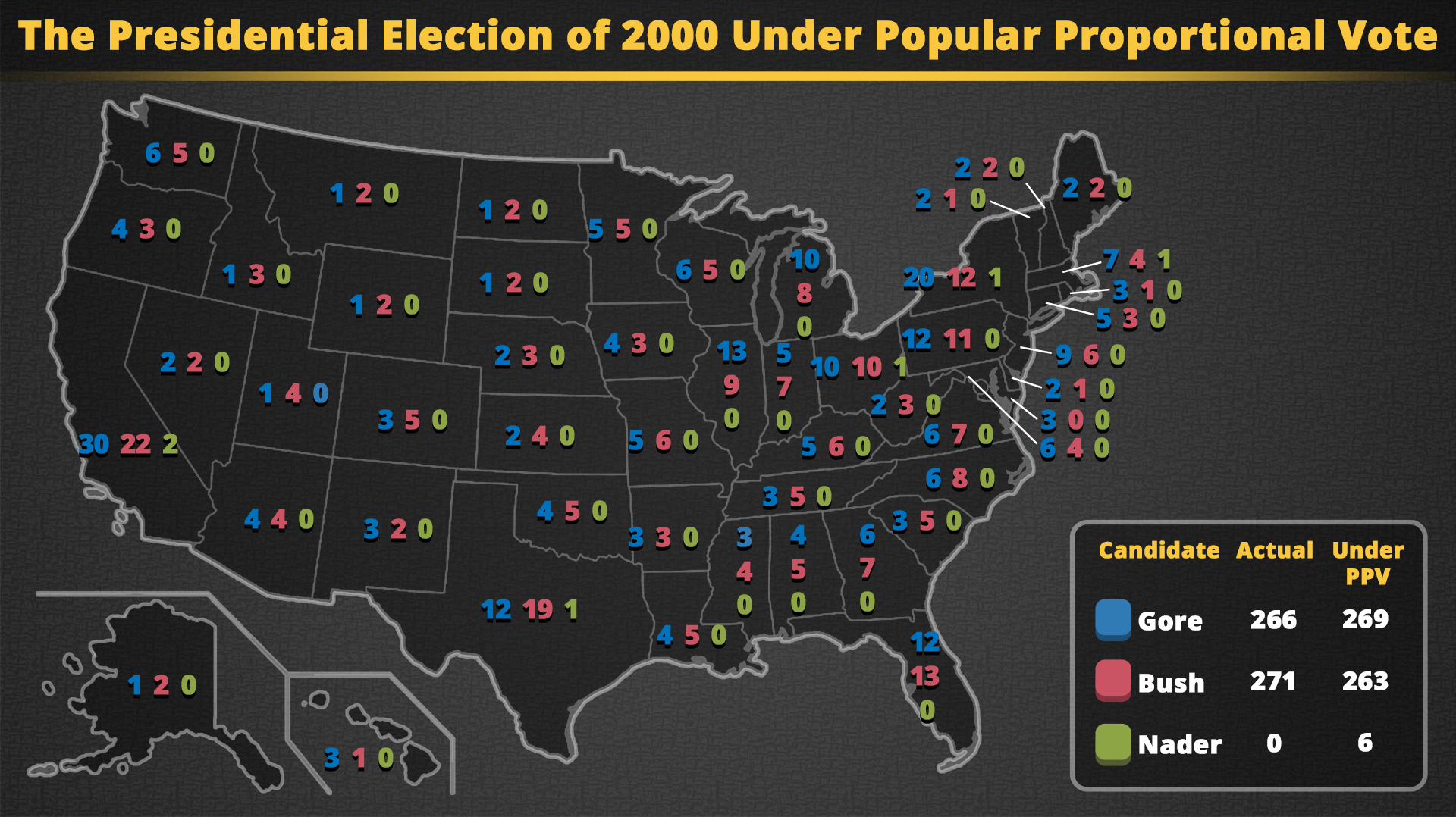

Could the Electoral College ever be abolished? It is sometimes argued that the Electoral College is outdated and impractical, and does not reflect the true will of the American population. This argument was particularly vehement after the 2000 election, in which Democrat Al Gore won a majority of the popular national vote by a very narrow margin over Republican George W. Bush (less than 500,000 votes nationwide), but the election outcome was ultimately decided when the US Supreme Court ruled that vote recounts in Florida should be stopped, giving the Electoral College victory to Bush (271 Bush, 266 Gore). This kind of discrepancy between the Electoral College and popular vote outcomes has happened only 4 times in American history, but it clearly goes against a sense of fairness and raises questions about legitimacy when it occurs.

Presidential Election of 2000 Under Popular Proportional Vote

Question:

How does America’s two-party system differ from the rest of the world?

Terms:

-

Two-party system

-

Democratic Party

-

Republican Party

-

Third parties

-

“Proportional representation”

National Union Ticket (Republican), 1864; New Jersey Ballot, 2010: The 2-party system is a fixture of the political landscape in the US. Although the Democrat and Republican parties have experienced some changes over time, they remain the parties of choice for most Americans. At left is the National Union Ticket, or Republican ticket, 1864. At right is a modern-day 2-party ballot from New Jersey, 2010.

It is unlikely that the United States will shift away from the winner-take-all model, so we are likely to see the continuation of a 2-party system. However, the specific 2 parties in that system have shifted several times over the course of US history, and there is no guarantee that the Democratic and Republican parties will hold their places as our major parties forever. If either of these parties is unable to hold together its coalition of loyal voters and a new party emerges that is more successful at gaining the support of a broad segment of the American electorate, we could see another party shift with one of these parties being displaced. The US continues to experience ongoing demographic changes, including a growing number of Hispanic American and Asian American voters. This, along with more liberal political attitudes among younger voters, particularly on social issues, means that both the Democratic and Republican parties need to strategize about how to attract and keep new generations of voters loyal.

Section 3: How Voters Decide

Section Question:

What are the influences on American voting?

Question:

Which Americans seem to vote and which do not?

Terms:

-

Comparing voter turnout

-

Mandatory voting laws

-

US voter turnout in various types of elections

-

Characteristics of the voter: age, education, income, and ethnicity

Question:

Which factors seem to influence American voters most?

Terms:

-

Following the public debate about issues

-

The way voters decide: partisanship, issues, and candidates

-

Party loyalty

-

Issues of national economy and national security

-

Single-issue voters

-

Candidate popularity and personal characteristics

-

Incumbency advantage

Melinda Jackson on the Funnel of Causality

Question:

How can voters learn about the candidates and their positions?

Terms:

-

Candidates’ use of types of media

-

Candidates’ use of debates

-

Party loyalty

-

Candidates’ websites for digital information

-

News sources for candidate information

“Quiet! It’s a Retrospective of Hostile Political Ads We May Have Missed.”

Further Reading

- Barbara A. Bardes and Robert W. Oldendick, Public Opinion: Measuring the American Mind, 4th ed. (or most recent), (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012).

- Shaun Bowler and Gary Segura, The Future is Ours: Minority Politics, Political Behavior, and the Multiracial Era of American Politics (Washington, D.C.:CQ Press, 2012).

- Angus Campbell, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald Stokes, The American Voter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960).

- James N. Druckman and Lawrence R. Jacobs, Who Governs?: Presidents, Public Opinion, and Manipulation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- William H. Flanigan, Nancy H. Zingale, Elizabeth Theiss-Morse, and Michael W. Wagner, Political Behavior of the American Electorate, 13th ed. (or most recent), (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2014).

- Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

- M. Kent Jennings, Laura Stoker, and Jake Bowers, “Politics across Generations: Family Transmission Reexamined,” The Journal of Politics 71, no.3 (2009): 782-799.

- Richard R. Lau and David P. Redlawsk, How Voters Decide: Information Processing in Election Campaigns (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Helmut Norpoth, William G. Jacoby, and Herbert F. Weisberg, The American Voter Revisited (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008).

- Arthur Lupia, Uninformed: Why People Know So Little About Politics and What We Can Do About It (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

- John Sides and Daniel J. Hopkins, eds., Political Polarization in American Politics (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2015).

- John Sides, Daron Shaw, Matt Grossmann, and Keena Lipsitz, Campaigns & Elections, 2nd ed. (or most recent), (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2015).